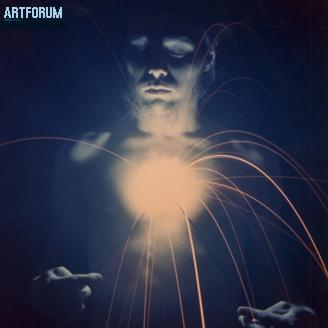

Cover image: Chris Burden, Doorway to Heaven, 15 November 1973

Artforum magazine, Volume XIV No. 9 (May 1976). The following article was published on pages 24-31.

© Copyright 1976 by California Artforum Inc.

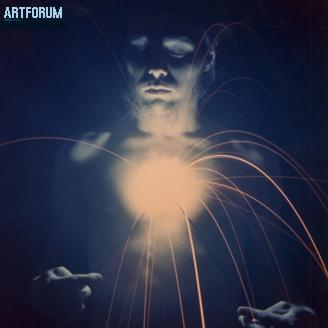

Chris Burden lies silently, inertly, on a triangular platform built into a corner of the Ronald Feldman Gallery. The platform is just an open shelf, 10 feet above the floor. It does not enclose him, though it does shield him from view if he is lying down, since the top of the platform is above the spectator's eye level. This is the space he must stay within in order to remain hidden. He is spending three solid weeks on this platform, cut off from all normal exercise, social activity, and food.

I enter the gallery and look up at the platform. It spans its corner diagonally and is painted white to blend with the walls. If I didn't know Burden was supposed to be on top of it, I would think that it was simply a piece of Minimalist sculpture, perhaps done by Robert Irwin, one of Burden's teachers. The assumption that he is there alters everything - but I don't know for a fact that he really is there. I become "it" in an unannounced game of hide-and-seek. I listen for any telltale rustling, any breathing noises. The many small sounds that fill the gallery are magnified by my attention.

The room is haunted. Thoughts tumble forth, drawn out by the vacuum of his withheld presence. While Burden is fasting, two leaders of the Irish Republican Army are in the seventh week of their hunger strike in a Belfast prison. They say they will fast to death to protest the British occupation of their country. At the same time, thousands are starving in East Africa and India, not as a symbolic gesture, but because drought has killed their crops and livestock. The reality of hunger in other parts of the world makes a disinterested esthetic appraisal of Burden's piece seem somewhat ludicrous, if not downright perverse. In this piece, as in his others, the motive has to be the key. His execution is beyond criticism: he need only endure the inactivity, isolation and hunger to carry the work through, and to large extent this process is concealed by the installation. The piece dominates its space effortlessly. Nothing is employed that is not absolutely essential. Even his timing, in terms of both his own oeuvre and the surrounding social climate, artistic and otherwise, seems apt. But why is he doing it?

The piece has many religious overtones. Mortification of the flesh, voluntary seclusion, trial by ordeal, these are the trappings of sainthood. The title of the piece itself, "White Light/White Heat," suggests the desert and mystical illumination [FOOTNOTE: I learned subsequently, from Burden, that the title actually comes from a song by the Velvet Underground.], and I recall that his previous show here was titled "The Church of Human Energy." It is hard not to think of this whole set-up as a metaphor for the Western notion of God: the Unseen Witness Above, whose presence is pervasive but nowhere revealed. Is Burden playing at being God?

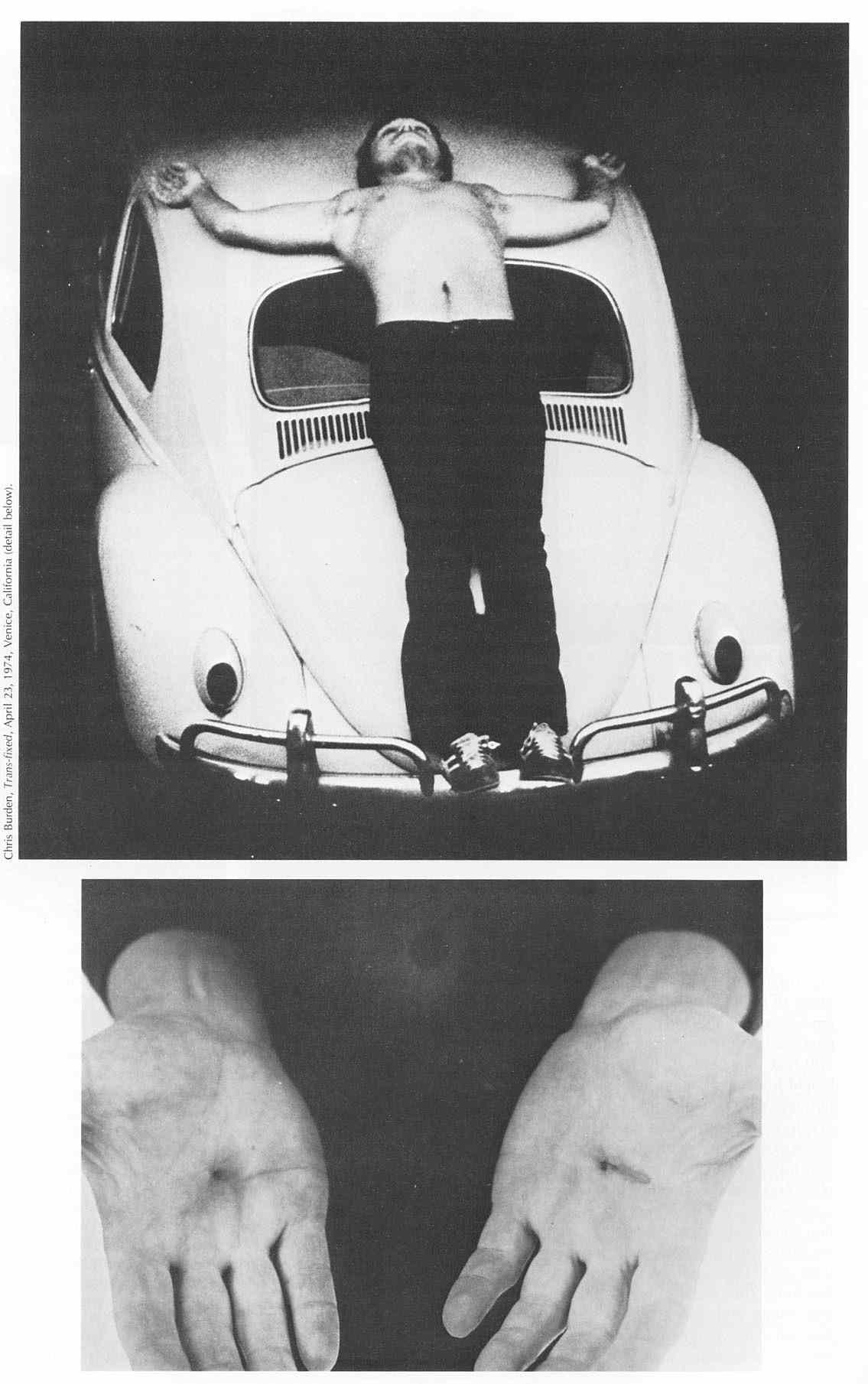

Other pieces of his have gone nearly this far, but have been qualified at some point by an element of self-mockery. I am thinking here of "Jaizu" (June 10 and 11, 1972, Newport Harbor Art Museum, California), where Burden, dressed in white and wearing dark, wrap-around sunglasses, sat motionlessly in a director's chair for two days while visitors were allowed in one at a time to contemplate him from cushions placed on the floor at the other end of the room, and of "Transfixed" (April 23, 1974, Speedway Avenue, Venice, California), where he was literally crucified, with nails driven through his palms, on the back of a Volkswagen that was pushed out of a garage for a few minutes, its engine roaring at full throttle, and then pushed back inside. In the first piece, what seemed to be an impassive beatitude on Burden's part was due largely to his inability to see anything (his sunglasses were painted opaque black on the eyeside), and further, he had placed a box of reefers by the visitor's cushions, offering them a cynically easy shortcut to their own beatitude as well. In the latter piece, replacing the cross with a Volkswagen effectively transformed a religious cliché into a diabolically droll, nightmarish masque: Jesus, indeed.

If there is religious metaphor in "White Light/White Heat," it is probably secondary, at least as far as Burden is concerned. A few days before he climbed up onto his platform, we talked about why he was doing this piece:

I've thought about this piece for a couple of years. Physically, it resembles the "Bed Piece" [February 18 - March 10, 1972, Market Street Program, Venice, California], but it's a refinement. In "Bed Piece," I had a bed put at one end of the room and I stayed there for 22 days. I didn't talk to anyone. There was a portable toilet for me at the front desk and I'd run up there after gallery hours, but most of my time was spent in bed. They left food for me, but a lot of times I didn't get fed because in their minds I had become an object... In the beginning it was real boring. It was very painful and hard to do, but I found that toward the end I actually got to enjoy it there... The shift from beginning to end was pretty mysterious to me and that's why I'm reinvestigating it. I'm trying to get to the crux of it. That's what this piece is about. I don't know exactly what's going to happen. I'm going to cut my contacts even further. In the "Bed Piece" there was always a visual reference. This piece won't have that. And I'm going to stop eating... One reason is to eliminate a lot of activity: food coming in, shitting. But fasting does something else. In the "Bed Piece" it was like I was this repulsive magnet. People would come up to about 15 feet from the bed and you could really feel it. There was an energy, a real electricity going on. I think that by fasting you can enhance those sorts of feelings - if they do indeed happen, and I kind of think they do... I have this fantasy, which may or may not be realized, that someone will come in off the street, not knowing my name, just doing a gallery tour, come in and see the platform and be able to feel that something's amiss. There'd be something that would nag at them and they could maybe feel my presence..." [FOOTNOTE: From the conversation we taped on February 4, 1975]

Interesting. Burden's explanation for fasting does not even touch upon its symbolic connotations, or its possible resonance with events happening simultaneously in other parts of the world. Apparently, fasting is for him a purely instrumental measure, taken to facilitate his descent into what can only be called the absolute ground-state of human existence, and not part of any outwardly directed religio-socio-political message. It is also interesting that he emphasizes his own immediate experience and his (subliminal) relationship with individuals actually present in the gallery to the exclusion of the larger secondary audience, who may be aware of his work from a distance. He does not mention the less direct but socially more penetrating effect of the work as a rumor, a "conversation piece," nor does he suggest that stimulating such secondary effects may have had anything to do with his decision to undertake it in the first place. Surely he must be aware of how readily his exploits are absorbed into public mythology. Knowing HOW this awareness is incorporated into his motivation and judgment would allow one to better differentiate between the incidental and the intentional content of his work.

As reasonable as his explanation is, and it does go a long way toward clearing up some areas of possible confusion, it still leaves many more general questions unanswered: why is he involved with this whole line of inquiry? What significance might his work have, beyond its significance for him? By what standards are we to judge it? And perhaps most importantly, what are the moral and esthetic implications of terming his work "good"?

Before leaving the gallery, I decide to leap into the air to get a better view. No, I still can't see him, but I do believe he's there.

• • •

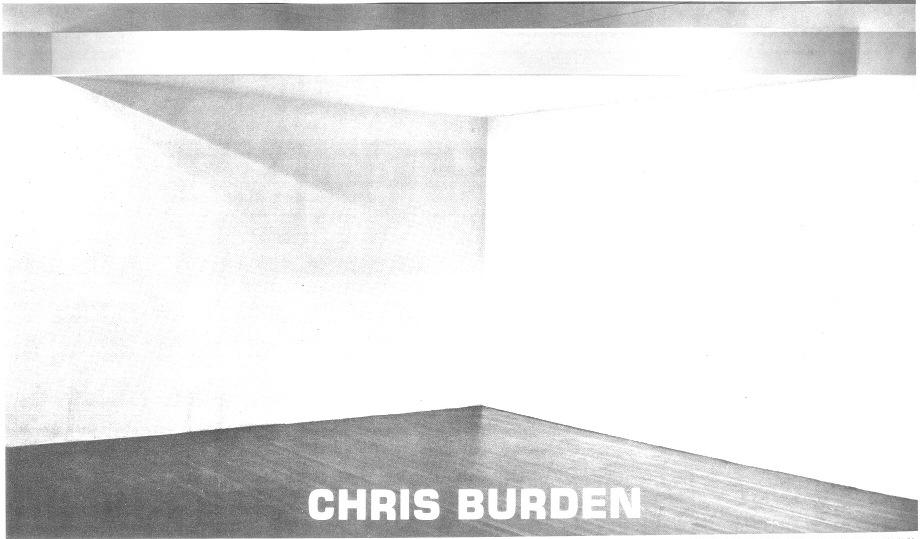

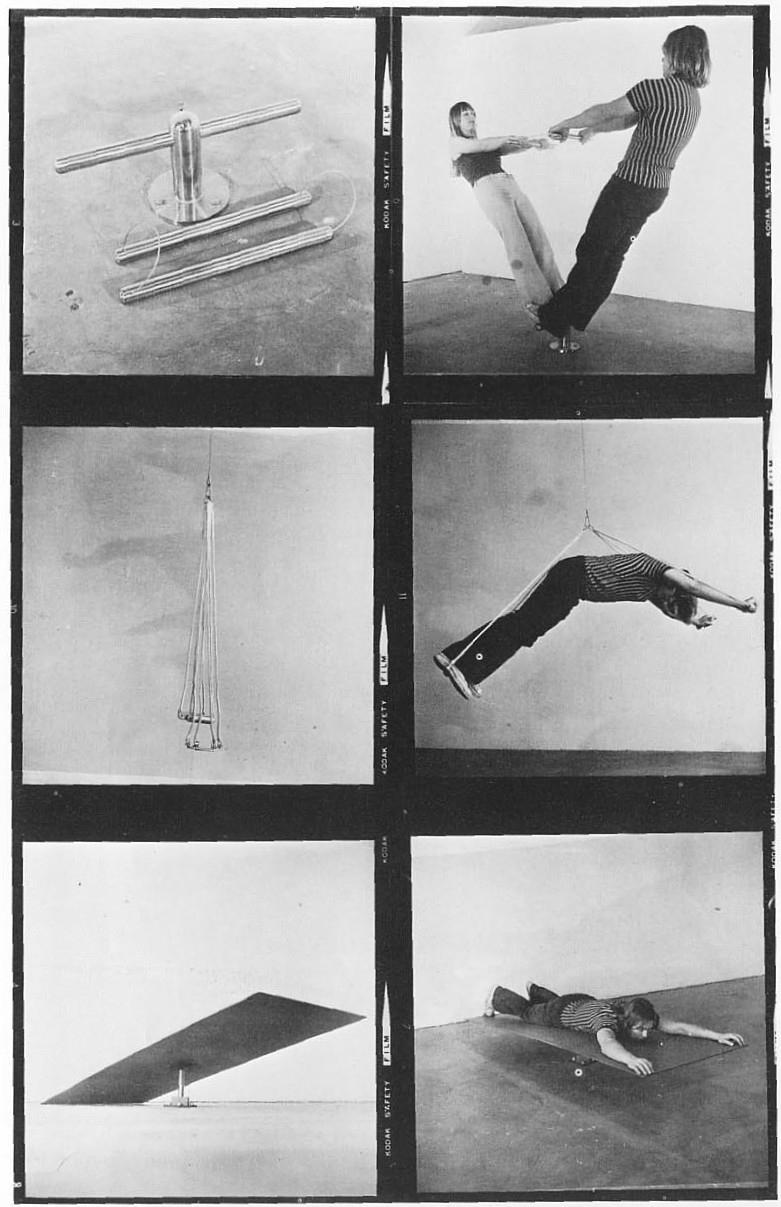

Chris Burden, untitled, 1968-9 (undergraduate project, Pomona College)

Burden's present type of work derives genetically from environmental sculpture rather than from theater. As an undergraduate art major at Pomona College, he had been working in a highly competent, but still relatively conventional, Minimalist mode. Two large pieces built on the school soccer field as part of his senior project (1968-9) may have marked the highpoint of this phase. The first consisted of a pair of arches made of hydraulically bent steel pipe set in concrete footings and connected by steel cables. The cables were canopied over with translucent plastic to form a tunnel 100 feet long and 20 feet wide, that diminished in height from nearly 8 feet at the larger end to only 2 feet at the smaller end. The piece clearly invited one to enter, and as one moved into it, the flattening curve of the tunnel gradually forced one to stoop lower and lower, so that by the time one had reached the other end, one was crawling through a very wide, squat passageway.

The other piece was similar in construction and probably was intended as a simple variation on the first. Steel pipes were set in the ground at 3-foot intervals to form a narrow corridor 11 feet high and 200 feet long. The structure was stabilized with guy-wires and linked with black plastic sheeting. But two unplanned elements entered into this piece that in the long run proved crucial:

"I thought of it as a corridor, but then things started happening that I didn't plan on. For one thing, it was getting vandalized, so I started having to live there to protect it. And the wind did a funny thing. It was such a big structure that the wind would hit one side of it and blow the plastic in, and this created some sort of vacuum that would suck in the plastic on the other side. So the whole thing was always pressed together. You couldn't see down it except on rare occasions. If you walked down it, it would engulf you, but if you started running, your body would make an air pocket that would push it open in front of you. It was like magic. The stuff would open in front of you and close behind you. That's when I realized that what I had made was not a piece of sculpture but something that had to be activated. These pieces were about physical activity, about how they manipulated my body. When I realized that, they stopped being sculptures and there was no reason to make them that big." [FOOTNOTE: From the conversation we taped on 4 February 1975]

Following up this insight, his next series of works, done in the graduate program of the University of California at Irvine, were quite different in character, resembling isometric exercise equipment more than sculpture. One consisted of a metal T-bar that bolted to the floor, on which two people were supposed to stand, and a pair of metal rods connected to each other by short cords. Holding the rods in their hands, the two people leaned away from one another and attempted to strike a common balance. "This balance point," Burden comments, "is very elusive and can only be maintained for a few seconds." It is tantamount to trying to balance a top-heavy triangle on its point.

Chris Burden, untitled, ca. 1970

A second piece consisted of four pairs of cables joined together at the end of another cable that attached to the ceiling. The free end of each pair had a stirrup for a person's hand or foot. The idea was to get into the stirrups and assume an arched position in order to hover somewhat precariously over the floor. The amount of effort required to sustain this position is inversely related to the degree of arching: the flatter the arch, the more difficult the task.

A third piece was simply a large sheet of aluminum with two small footholds, supported in the center by a pivot that bolted to the floor. By lying down on the sheet and carefully adjusting one's position, one could balance on the pivot for an indefinite period of time.

All of these pieces attempt to establish a delicate sensual interplay between body and apparatus. They are extremely responsive to changes in position and muscle tension and seem to have been expressly designed to amplify these changes. They are not primarily to be looked at: they are to be donned and used. By drawing the viewer (viewer is obviously no longer the right word) into the work, giving him an active, literally constitutive role, Burden seemed to be trying to overcome the detachment and visual/intellectual distance usually entailed by object sculpture and replace it with an immediate kinesthetic involvement. Trading formal autonomy and stasis for dynamic equilibrium and engagement, his transition out of sculpture was well underway.

But not without problems. As these apparatuses were still one-of-a-kind, custom-made objects, and very elegant ones at that, most people continued to regard them as conventional sculpture, complete in themselves. While he had tried to make their intended use so self-evident that no further instructions or inducements were needed, it didn't quite work. People tended to read them as metaphors for activity rather than as literal opportunities. Eventually Burden hit on a two-part strategy for dealing with this misunderstanding. The first was to use equipment that already existed so that it would not attract attention to itself as a specially invented form. The second was to further reduce the distance between himself, the experience he wished to convey, and the audience, by enacting the work himself.

The first definitive piece of this new kind was the "Five Day Locker Piece" (April 26-30, 1971, University of California at Irvine). The site chosen was one of a number of storage lockers already installed in a school studio. He placed a five-gallon container of water in the locker above and a similar, initially empty, container in the locker below (he had access to both through concealed tubes). Burden entered his tiny (2' x 2' x 3') locker knowing that he would emerge in five days, but without knowing what the experience would be like or how others would respond:

"It was an experiment. I wanted to see what would happen. I thought this piece was going to be an isolation thing, but it turned into this strange sort of public confessional where people were coming all the time to talk to me. At first, just my friends and the other grad students knew about it. Then it started building up, rumors were spreading. The university's a pretty big place and people who weren't interested in art, specifically, came over just to see this guy locked in a locker. I think that the further away you were from this, the more strange it seemed, and I noticed that when people actually came to talk with me, they were reassured in a way... Pretty soon, the campus police were involved, and they didn't know what to do. And then, the Dean of Fine Arts found out about it and he was real panicky. There was a debate about whether or not they should try to pry me out with crowbars. And there was nothing I could do. Just toward the end I got panicky myself. I started getting that weird feeling that a REAL crazy was going to come and do something to me. There were periods of time when I was alone and I knew my vulnerability might inspire someone to do something crazy. But that was only toward the end..." [FOOTNOTE: from a lecture at the Rhode Island School of Design, November 12, 1974]

Nothing crazy was done to him, however, and he emerged, hungry, cramped and tired at the predetermined time.

While Burden's work from 1969 to 1971 appears to develop rapidly in a step-by-step progression, with each series implementing the insights of the preceding series, his work since "Five Day Locker Piece" seems to fan out laterally, expanding in range and diversifying in content, but without departing significantly from a single nexus of ideas. No longer confined to the materials and values peculiar to sculpture, he has gone on to devise dozens of performance events that are notable for their space-filling energy, their stark simplicity, and their perplexing, audacious amorality. Each one is based on a premise: spending five days in a locker, breathing water, flirting with electrocution, etc. The premise is the seed of a concrete situation, a predicament clearly set apart from the stream of normal life activity. It gives the work coherence, even while leaving the outcome somewhat unpredictable and open-ended. Each premise involves an element of risk - not just the academic risk of transgressing "the limits of art," but the very real risk of bodily injury, public failure, occasionally even of criminal prosecution (e.g. "Deadman," November 12, 1972: "At 8 p.m. I lay down on La Cienega Boulevard [in Los Angeles] and was covered completely with a canvas tarpaulin. Two 15-minute flares were placed near me to alert cars. Just before the flares extinguished, a police car arrived. I was arrested for causing a false emergency to be reported...").

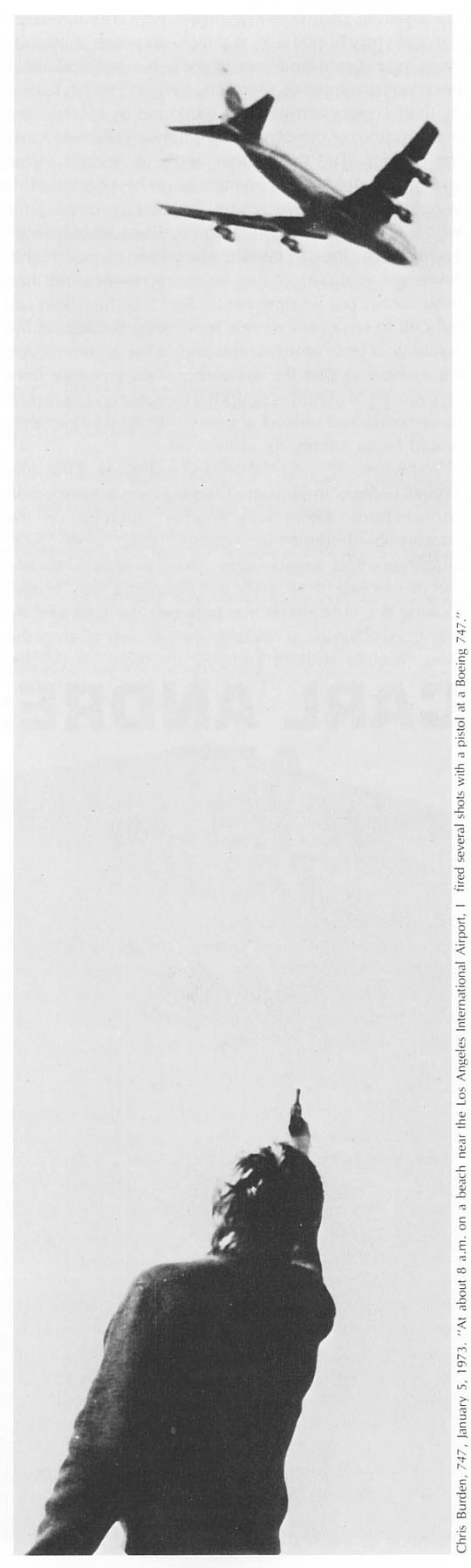

[FOOTNOTE: All subsequent passages describing his work that appear in quotes are taken from 71-73, ©1974 by Chris Burden, unless otherwise noted. Charges against Burden were dropped when the jury failed to reach a verdict. More recently, the FBI questioned him about his piece "747," in which he fired several shots at a jet as it took off from the Los Angeles International Airport. Since he was out of range at the time, they seem to have decided not to prosecute.]

Every piece centers on some sort of iconoclastic behavior that floods its surroundings with an almost palpable atmosphere of anxiety and fascination and, at the same time, grounds the work in a level of experience that is conspicuously extra-cultural, primal, atavistic. No piece is ever repeated. No piece is ever rehearsed.

Without meaning to suggest that this scheme has any explanatory significance, his work since "Five Day Locker Piece" can be broken down into three relatively distinct categories, according to his role in the public presentation. The first, and most prevalent, type involves Burden in a passive role. These are based not on an activity so much as on the suspension or subtraction of activity, and they often acquire "scale" through their extended duration. Some examples of this type are "Bed Piece," "White Light/White Heat," and "Disappearing" (December 22-24, 1971: "I disappeared for three days without prior notice to anyone"). The second type is the opposite and includes many of his best-known works. These are organized around a single drastic, often reckless act, and, in contrast to the first type, they are almost always very brief. A few have been virtually instantaneous, like "Shoot" (November 19, 1971, F Space, Santa Ana, California: "At 7:45 p.m. I was shot in the left arm by a friend") and "Doorway to Heaven" (November 15, 1973: "At 6 p.m. I stood in the doorway of my studio facing the Venice boardwalk. A few spectators watched as I pushed two live electric wires into my chest. The wires crossed and exploded, burning me but saving me from electrocution."). The third group is scattered between these two extremes. The emphasis here is on neither activity nor passivity per se, but on their equilibrium, on the situation as a whole, and the success of such pieces depends on their evocative power as images. Many of them are tableaux vivants, like "Transfixed," "Jaizu" and "Deadman."

Chris Burden, Transfixed, 23 April 1974, Speedway Avenue, Venice, California

One recent piece that does seem to indicate a new and potentially significant departure is "Poem for L.A.," a 10-second videotape which was broadcast some 60 times as a commercial "spot" on KHJ-TV and KTLA-TV in Los Angeles between June 23 and 27, 1975. Burden had previously purchased air-time in 1973 to show a 10-second filmclip of "Through the Night Softly" (September 12, 1973, Main Street, Los Angeles: "Holding my hands behind my back, I crawled through 50 feet of broken glass. There were very few spectators, most of them passersby."), but this was really only an adaptation of a work not done specifically for television. "Poem for L.A.," shot on 2-inch color tape and electronically edited, was. It opens with a close-up of Burden's face. He says, "Science has failed." These words then appear on the screen spelled out in block letters. Burden reappears and says, "Heat is Life," and these words appear on screen. He appears once more and says, "Time kills." Words come on screen, followed by the credits, and it is over. (During the week of its broadcast, the two television stations carrying it were deluged with puzzled phone calls.)

Retracing his evolution from the large, outdoor sculptures, through the apparatus pieces, to the more recent tension-charged situations, it ought to be clear that Burden's present manner of working represents a genuine synthesis, an ingenious (if somewhat harrowing) convergence of form, experience and will, the foundations of which were laid well before he came into the public eye. Beginning almost fortuitously with the corridor piece, he realized the extent to which his sculpture shaped and was shaped by activity. The apparatus pieces refined and schematized this interaction and drew the spectator more explicitly into the substance of the work. Finally, the mediating object disappears altogether and we are brought face-to-face with the enactment of the work, accessories to the process-becoming-fact. His work still retains something of a sculptural sensibility, as can be seen in his continuing pre-occupation with physical stress, with the plasticity of human feelings and sensory experience, and also, less obviously, in the non-narrative, unitary time forms that underlie most of his work. But this sensibility is geared to an environmental scale, has internalized its psycho-social impetus, and thus, no longer distinguishes so sharply between matter and man. (Joseph Beuys' felicitous term "social sculpture" is applicable here.) Although the logic of this trajectory is probably more obvious in retrospect than it was at the time - he was almost certainly guided by flash intuition and instinct as the links fell into place - it nonetheless reveals an astute, disciplined and rigorously self-critical mind at work. This does not in itself establish the value of the work, for Burden or for others, nor does it even begin to exhaust the possibilities of interpretation, but it does show that we are dealing with something more than the nihilistic flailings of a demented naif.

While Burden's whole stylistic development seems to have been conditioned by a desire to overcome esthetic detachment (and, more specifically, the over-intellectualized program of orthodox Minimalism), the result of this desire has not been an absolute immediacy in each and every piece so much as the ability to control the quality and degree of immediacy appropriate to a given situation. That is to say, instead of eliminating contemplative distance completely, he freed it for use as a thematic variable. Many of his most interesting pieces have depended on his control over the audience interface as a key part of their structure and content.

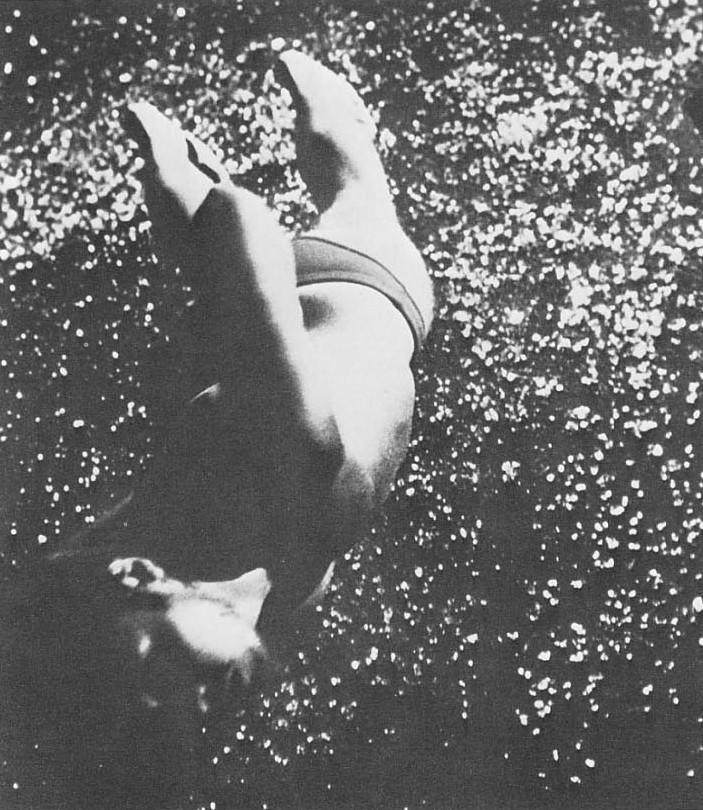

In "Velvet Water," for instance (May 7, 1974, School of the Art Institute of Chicago), undoubtedly one of his most effective and disturbing works, Burden was seated next to a small sink full of water, only a few feet from the audience, but visually concealed by a row of low cabinets. Two video cameras picked up his image and relayed it to a bank of five monitors in another part of the room. After announcing what he intended to do, he submerged his face in the water and repeatedly tried to breathe it. The piece ended a few minutes later - it seemed to last much longer - when he collapsed, exhausted and unable to continue. The people in the audience knew that what they were watching on the monitors was really happening: they could hear the sound of his choking and gagging directly, live, right next to them. But Burden's use of closed-circuit television had the effect of objectifying the performance artifice, shifting attention away from his bone-chilling convulsions and onto the culturally sanctioned voyeurism and complicity of the spectators. The electronic link between him and the audience tacitly implicated them in his ordeal, even as it seemed to distance them from it sensually. "Velvet Water" has as much to do with the ethical limbo of the spectator role as it does with the experience of drowning.

The issues of access and distance also come into play in Burden's documentation of his work. A purist might argue that if his concern is really with the immediate, existential moment, he shouldn't document the work at all. It should endure only as a memory, absorbed into the lives of those present at the time and denied to everyone else. This argument might hold if all access to the work could in fact be confined to its immediate audience, or, failing that, if the second-hand information finding its way into general circulation were reasonably accurate and ungarbled. But Burden discovered early on that neither condition obtained. He was forced to choose between a theoretically pure stance, maintained amid widespread misrepresentation, and a somewhat compromised stance, with some chance of keeping the record straight. Never one to stand on theory, he chose the latter.

But having decided to document his work, another problem arises: if there is any hint that a given action was intended to be seen only at a remove - that it might therefore be only a charade - its credibility as a lived experience (and, by inference, the credibility of all his other recorded works) is called into question and its impact irrevocably lost. Thus, Burden must take special care to establish the documentation's limited function in the overall scheme of things, i.e. establish that the live event is not subservient to its more durable and distributable complement, and, perhaps more importantly, that the event was not undertaken simply to be recorded. A quick look through 71-73, his self-published catalogue of work from those years, suggests that he has certainly taken these points to heart. Many of the photographs are blurry, scratched, over- or underexposed - barely adequate. The brief verbal descriptions accompanying them are often more vivid and informative than the pictures themselves, though they give even less sense of mood and setting. The videotape compilation of his work that was shown at the Feldman Gallery last year has similar shortcomings. It includes, for instance, a short film of "Shoot," his most notorious piece and the one that first brought him to international attention. The image quality is grainy and further degraded by the transfer onto tape, and on the soundtrack, the report of the rifle is all but lost amid the informal chatter and milling around of the spectators. This is not to say that the casual, and frequently underwhelming quality of the documentation detracts from the work itself. Quite the contrary. It seems to corroborate McLuhan's thesis that a low-definition "hot" image evokes a greater degree of viewer empathy and fantasy-projection than a high-definition "cool" one. By acknowledging the real distance between the live event and the secondary audience, instead of trying to compensate for it, Burden's documentation conveys a hype-free authenticity even as it tends to mythify the work by omitting distracting details.

Chris Burden, Through the Night Softly, 12 September 1973, Main Street, Los Angeles: "Holding my hands behind my back, I crawled through 50 feet of broken glass. There were very few spectators, most of them passersby."

John Dewey's seminal Art as Experience provides a singularly useful backdrop for a critical discussion of Burden's work. In fact, even though it was written some 40 years ago, and even though Burden says he has never read it, many of its arguments so clearly anticipate his kind of work that its relevance is quite uncanny:

"The esthetic is no intruder in experience from without... it is the clarified and intensified development of traits that belong to every normally complete experience. This fact I take to be the only secure basis upon which esthetic theory can build.

"What is done and what is undergone are thus reciprocally, cumulatively, and continually instrumental to each other. The doing may be energetic, and the undergoing may be acute and intense. But unless they are related to each other to form a whole in perception, the thing done is not fully esthetic.

[FOOTNOTE: John Dewey, Art as Experience, New York, 1958 (©1934 by John Dewey). Passages quoted are from pp. 46, 50 and 11, respectively.]

For our purposes, the first passage quoted above is especially helpful, as it suggests that our ability to grasp an experience esthetically hinges on its clarity, intensity and strength as a Gestalt, and Dewey even goes so far as to elevate this to the status of a First Principle. At least as a starting-point, we might take a look at Burden's work in light of these criteria.

As for intensity, there can be little doubt about that. Each of his pieces is a crucible in which life and life-threatening forces, power and vulnerability, are locked in a paroxysm of mutual subversion. Unencumbered by narrative or didactic superstructures, the whole spectrum of somatic fears and fantasies is at his disposal and he seems almost irresistibly drawn to those that stimulate the most adrenalin. It is difficult to think of another living artist whose work projects such visceral intensity and bite.

Clarity, however, is another matter. While Burden obviously devotes a great deal of effort to condensing and essentializing his concepts, the result is not so much total clarity as highly refined ambiguity. There is never any confusion about what he is nominally trying to do, but one cannot ignore the fact that his actions, clear in themselves, are deliberately and obdurately problematic. Like most reductivist art, his work is under-articulated. That is, the information presented is so limited that one set of facts may suggest - indeed, may encourage - a number of conflicting interpretations and offer no means of determining which were intended by the artist. Moreover, no physical surface encloses the work, separating it from the artist or from the audience. Both are immersed in it, and inaccessibly private responses, feelings and insights are woven into its basic structure. Nor can one distinguish between those qualities that are specifically attributable to the work from those that are ambient or latent in the environment. In other words, many factors limit the work's clarity. But I would contend that Burden does push the process of clarification as far as his methodology permits, and that his work is substantially enriched by those ambiguities that remain: far from representing defects, they are precisely what gives the work its purchase on our interest.

Many of the same considerations also apply to the formation of a strong Gestalt - so much so that I will not bother to enumerate them again. On the other hand, many additional factors, not bearing on clarity, do serve to set the work apart from the general flux of experience: the extremism of his ventures (their "beyond the pale" quality, their scale), the premeditation, the stylistic consistency, the documentation, etc. Suffice it to say that even though they derive meaning from and, in turn, impinge upon a much larger field, each of his pieces constitutes a conceptually stable, singular and finite course of action, and this endows them with the character of a Gestalt.

Actually, their Gestalt character is so pronounced that an entirely different sort of question may be raised. Since the time Dewey wrote, we seem to have developed a willingness to accept as art, experiences that are, by his standards, rather loosely formed. Methods of chance composition, serial imagery, systems esthetics, and so on, have all extended our sensibility to the point where formal closure is a stylistic option, a matter of perspective, perhaps, but no longer an absolute necessity. With this in mind, one might ask why Burden chooses to cast his ideas into such emphatic, almost monolithic integrities. Is it just a habit transposed from sculpture? Is it for impact?

Two other answers occur to me that seem to go further. The first is that the sheer ferocity of his work requires that its esthetic aspirations be made as explicit and incontrovertible as possible. (The reason for this is not hard to fathom: the extent to which we are able/willing to view his actions esthetically in large measure determines the extent to which we are able/willing to set aside our moral judgment. That is not to say that the moral and esthetic realms are mutually exclusive, only that our response to his work is necessarily context-dependent.) The second is that that strong Gestalt figuration is being used for something beyond merely qualifying the work for apprehension as art.

From an external (i.e. public) point of view, the Gestalt not only serves to estheticize the experience; it acts directly, independent of context, to mollify the application of everyday behavior norms. By presenting a clearly ordered, self-consistent yet anomalous event, that is, an episode bound and governed by its own inner logic, it is possible for Burden partially to thwart the reaction his audience would surely have if the episode were less sharply delineated. The disparity between the work's impeccable logic and the spectator's common sense is one that he cultivates assiduously. Beyond inspiring an acutely conflicted (and, where one can appreciate it, exquisite) bewilderment, this skewness puts one at a critical impasse, an exasperating equivocality from which it is difficult, if not impossible, to make any sort of value judgment. Burden balances attraction against repulsion, openness against inaccessibility, so as to suspend his work in its own indomitable force-field.

But, in the end, I think that the design of his work has more to do with the requirements of his own experience than it does with public efficacy. We can only understand the centrality of the Gestalt if we are able to see it from his perspective, and this leads inevitably to questions of motivation and purpose. Unfortunately, Burden is reluctant to talk about such matters - not evasive so much as sincerely at a loss to describe what meaning his work holds for him. Certainly, words are totally inadequate to describe any artist's relationship with his work. They may even pollute the process they are invoked to describe. But the very nature of his work forces one to speculate.

Like anyone else who has heard about or experienced more than two of his pieces, I have some theories of my own. So let me speculate. I think that to some extent Burden views his work as a means of pre-empting fate. The strategy is actually quite simple. By setting up situations that test the capacity of his will, there are only two possible outcomes: either he will emerge victorious, having affirmed his mastery over the situation, or, should it get the best of him (which it hasn't ever yet), he can still fall back on the knowledge that at least he created his predicament himself. Either way he is responsible for, and in that sense has power over, his fate. Since fundamentally there is no doubt about his responsibility/power, he is able to take extraordinary liberties with the situation, turn it against himself, up the stakes to his mortal limit: he's got control to burn. More importantly, I think he must take risks to prevent the situation from collapsing into an empty solipsistic tautology ("I am that I am"), to entrench it in objective life-transformation. There can be no doubt about the indelible and mutually reinforcing impact of his work on the shape of his life. (The risk also serves to attract the interest of other people, expanding the size and import of the entire situation.) Where does the Gestalt fit into the picture? It is what makes it all practicable. The only way for Burden to reclaim control of his fate is to break the task down into managable chunks, take it on piece by piece, so to speak. He's no fool: he knows his limits and he limits his risks accordingly. He constructs his situations in such a way as to create an approximate symmetry of power between himself and his predicament; in other words, he molds and abstracts his "adversary" into a finite oneness like himself. This is a reciprocal process of humanizing adversity and materializing the will, and it leads to that blurring of the man/matter distinction I mentioned earlier.

Now, I realize that this analysis is awfully facile. It obscures the tremendous psychological and physical difference between disaster and accomplishment (though the work often seems to obscure that distinction as well); it emphasizes the way Burden might benefit personally from these transactions with fate without giving equal attention to the way he might benefit socially; it also fits some pieces better than others. But it does ring true on one very important point, namely that the ostensive elements of pain, risk, violence and vulnerability are less salient to the conception of the work than are self- and situational control. To be more precise, the former are only means to the latter ends.

This desire for power over one's life is a perfectly understandable impulse. It even has a long and venerable tradition as a Romantic theme in art. But there is one sticky point that we can no longer avoid confronting: these control situations that Burden creates typically include other people. Where they are just casual passers-by, as in "Through the Night Softly," the inclusion is so weak that there is not much to be said about the morality of his relationship to them. Where they are willing spectators, as in "Velvet Water," the dynamics are more complex, though probably no more invidious than those found at the circus during a highwire act. But consider a piece like "The Visitation," which was presented at Hamilton College (Clinton, NY) on November 9, 1974. I would like to describe it in some detail, not just because it is a perfect illustration of the issues at stake here, but because it is one of his shrewdest and most superbly realized works.

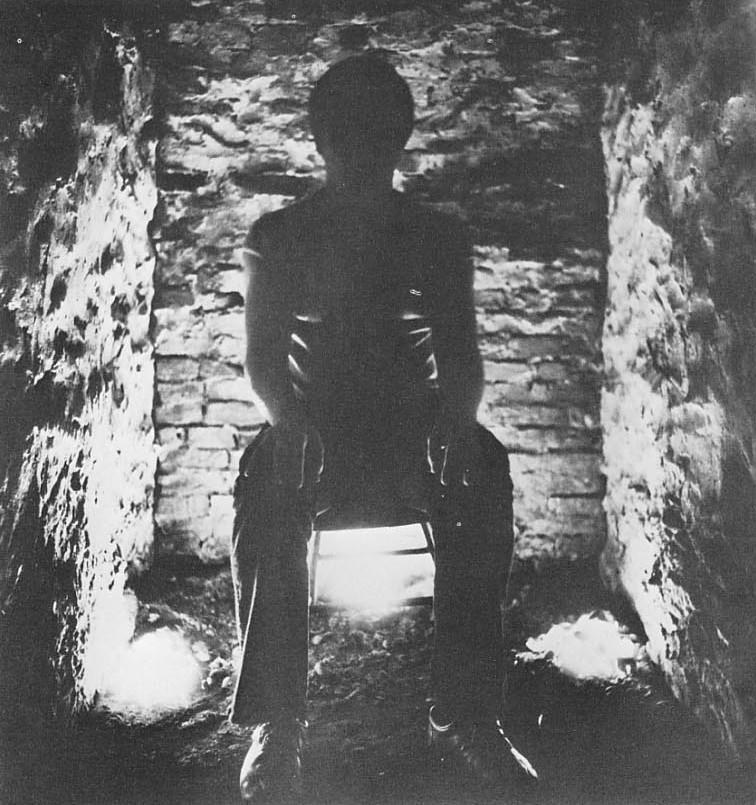

Chris Burden, The Visitation, Hamilton College, Clinton, NY, 9 November 1974

Burden had been invited to participate in a group show of California artists at the college's art gallery, and an announcement that he would be making his contribution at the opening attracted a large crowd. Initially, only one person, the organizer of the show, knew what the arrangements were, and when anyone at the opening asked about what was to happen, he led them down to the basement, where they were met by Burden's wife, who stood next to a locked door. The door led into a dirt-floored boiler-room that was quite hot and pitch dark - except for a single ray of light that extended from a crack between the top of the door and the door-frame, down the length of a wall. Only one person was allowed beyond the door at a time. As they entered the room, the door was shut and locked behind them. The beam of light ended at an alcove between two massive pillars supporting the fireplace upstairs. Burden was seated there, surrounded and faintly illuminated by glowing embers. When he was discovered, he introduced himself and talked casually with each visitor for as long as he or she wished.

About 15 people actually saw Burden. Their experience was probably one of disorientation and trepidation as the door closed and locked behind them, followed by relief that the encounter proved to be so painless and intimate. But the effect on those left outside was overwhelming. Word of Burden's presence downstairs had spread quickly and scores of people jammed the space in front of the boiler-room door. Without any instructions to do so, the few who did get to see him refused to say anything about what had happened to them, thus fueling the crowd's fantasies. Windows in other parts of the basement were broken by people clamoring to get in. The opening was totally consumed by the piece. Capitalizing on the drawing power of his reputation, the tension between the crowd's expectations and the strict limitations he placed on their access to him gave the piece its spatial charge. The fabulous spectacle that the crowd had come to expect from Burden, based on what they knew about his past work, was indeed provided, but they turned out to be it.

In presenting this piece, Burden had the active cooperation of the museum director and the sponsoring institution. He had the unwitting, but completely voluntary cooperation of the students. He did nothing violent, self-destructive or illegal. No one was injured. He actually used much less force than the average rock-sculptor uses in carving a statue. And yet the manipulative, autocratic aspects of the work are obvious. We might ask ourselves a number of questions:

To what extent are we justified in suspending our moral judgment when the material being worked is human?

To what extent, if any, and under what conditions, does morality have a higher claim on our actions and reactions than esthetics?

To what extent can the "right" to exploit oneself be prevented from generalizing into the right to exploit one's relationships with other people?

To what extent is the relationship between artist and audience qualitatively altered by the removal of the mediating object?

To what extent is the special nature of this relationship lost in the shift from symbolic to literal expression?

These are basic questions, but I honestly don't know the answers. One thing that makes them particularly difficult is that, while many people may feel that Burden's tendency to treat himself and others in a calculated, objectified manner is scandalous, if not pathological, it is something that I feel I both understand and sympathize with. For one thing, it is only the other side of the almost overbearing intensity and care he brings to his work. He is not an insensitive person, and I don't think it is going too far to say that his attitude reflects a profound intuition of the folly of taking humanistic (read: middle-class "cult of caution") values as an absolute frame of reference. The merging of man and matter proceeds apace, not just in Burden's mind, but almost everywhere one looks, from biochemistry to crafts, from Zen to resource management. The old dichotomy between nature and culture is already just a retardataire fiction. Seen from this perspective, Western popular morality is a thoroughly sanctimonious ritual, a canonization of species chauvinism whose contradictions grow more transparent with every extension of technological power. It fosters the illusion that man occupies a privileged place in Creation, that he lives by laws of his own making - and most seriously of all, it legitimizes the transfer of life-style inefficiencies and expedients to the nonhuman part of the environment, where the extravagant damage we cause arouses only the mildest feelings of guilt. Of course this is all completely untenable.

In one sense, Burden's work may be seen as a metaphor for human autocracy forced to re-absorb its formerly exported conflicts. In another sense, it may be seen as a signal that individual will, no matter how forcefully manifested, has slipped below the threshold of historical impact, that "The System" is set on a course that no one can either understand or affect, that the will only has meaning as an esthetic divertisement. In yet another sense, it may be part of the leading edge of what Toynbee has called "rebarbarization," one of the unpleasant intermediate stages of our reintegration with the physical world. Perhaps reading world-historical trends into Burden's work is as ridiculous as fixing narrowly on its technical novelty as art. But because it moves at such an emblematic, elemental level and speaks with such Delphic self-assurance, the temptation to do so is quite irresistible. Whatever it is that Burden thinks he is trying to do, he has forced me to rethink the values by which I live, and for that I am deeply grateful.

-----------------------------------------------------

Robert Horvitz is an ordinary housewife who draws. Other writings...